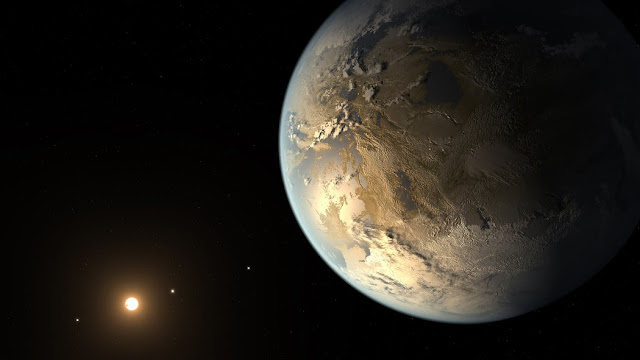

Earth like planet discovered by NASA, says it is "Earth's bigger, older cousin"

NASA said Thursday that the scientists on the search for extraterrestrial life have discovered “the closest twin to Earth” outside the solar system. The Kepler spacecraft that has spotted "Earth's bigger, older cousin" is the first nearly Earth-size planet to be found in the habitable zone of a star similar to our Sun.

In 2009, the $600 million Kepler mission was launched with a goal to survey a portion of the Milky Way for habitable planets.

From a vantage point 64 million miles from Earth, it scans the light from distant stars, looking for almost imperceptible drops in a star's brightness, suggesting a planet has passed in front of it. However, confirmation of their true planetary status requires observations by other instruments, typically looking for slight shifts in the motion of the host suns.

NASA Researchers, SETI Institute and several universities announced the new exoplanet along with 12 possible “habitable” other exoplanets and 500 new candidates in total.

Named Kepler 452b, the new planet is “the closest twin to Earth, or the Earth 2.0 that we’ve found so far in the dataset”, said John Grunsfeld, Associate Administrator for NASA's Mission Directorate.

Jeff Coughlin, a SETI scientist said “This is the first possibly rocky, habitable planet around a solar-type star." The previously discovered 11 exoplanets of a similar size and orbit travel around stars that are smaller and cooler than the sun. The first exoplanet orbiting a distant star was discovered in 1995.

Seven candidates appear to orbit solar-type stars, Coughlin said. “Time will tell if they stand the tests.”

“It is the closest thing that we have to another place that somebody might call home,” said Jon Jenkins, a Nasa scientist.

The discovery “takes us one step closer to understanding how many habitable planets are out there”, said Joseph Twicken, a Seti scientist also on the Kepler mission.

According to the research, it suggests Kepler-452b has five times the mass of Earth, is about 1.5bn years older, 4% more massive and 20% brighter and has a gravity that is twice as powerful as our own. As stars age they grow in size and energy, throwing more heat at the objects in their orbit.

The new planet is about 1,400 light-years from Earth in the constellation Cygnus. NASA says it is about 60% bigger than Earth and is situated in its star's habitable zone, where life-sustaining liquid water is possible on the surface of a planet.

A visitor there would experience gravity about twice that of Earth's, and planetary scientists say the chances of it having a rocky surface are "better than even", likely with active volcanoes, and has a thicker atmosphere with greater cloud cover than the Earth.

The scientists said that the new planet receives 10% more energy than the Earth, which means it could provide a glimpse into a burning, waterless future on Earth.

Doug Caldwell, a SETI Institute scientist on the Kepler mission said “Kepler 452b could be experiencing now what the Earth will undergo more than a billion years from now."

“If Kepler 452b is indeed a rocky planet,” he said, its location “could mean that it is just entering a runaway greenhouse phase of its climate history. Its ageing sun might be heating the surface and evaporating any oceans. The water vapor would be lost from the planet forever.”

Coughlin said that thoroughly examining the catalog will help astronomers “determine the number of small, cool planets that are the best candidates for hosting life”.

“We’re trying to answer really fundamental questions,” Grunsfeld said. “Where are we going as human beings, and of course the really grand question: are we alone in the universe?”

Missions are being prepared to move scientists closer to the target of finding yet more planets and cataloging their atmospheres and other characteristics.

In 2017, NASA plans to launch a planet-hunting satellite called TESS, a survey satellite that searches the nearest solar systems for exoplanets. With increasingly powerful telescopes and satellites, scientists may someday be able to “make the first primitive maps of an Earth-like planet”, including details of “whether they have oceans, clouds, perhaps even seasons”, says Grunsfeld.

Didier Queloz, professor at Cambridge said the team has only reasons to be hopeful and confident for planets that resemble Earth even more closely: “This is just the beginning of a very long journey.”